A fascinating facet of impressionism

European Landscape pain

ting is a Dutch invention. By the time of French Impressionism at the latest, when open-air painters celebrated the fleeting moment as the epitome of modernity, Dutch artists were inescapably challenged to react. The exhibition “Clouds and Light: Impressionism in Holland” explores this European dialogue, tracing the development of Dutch art from the 1840s to the 1910s in its conversation with Impressionism.

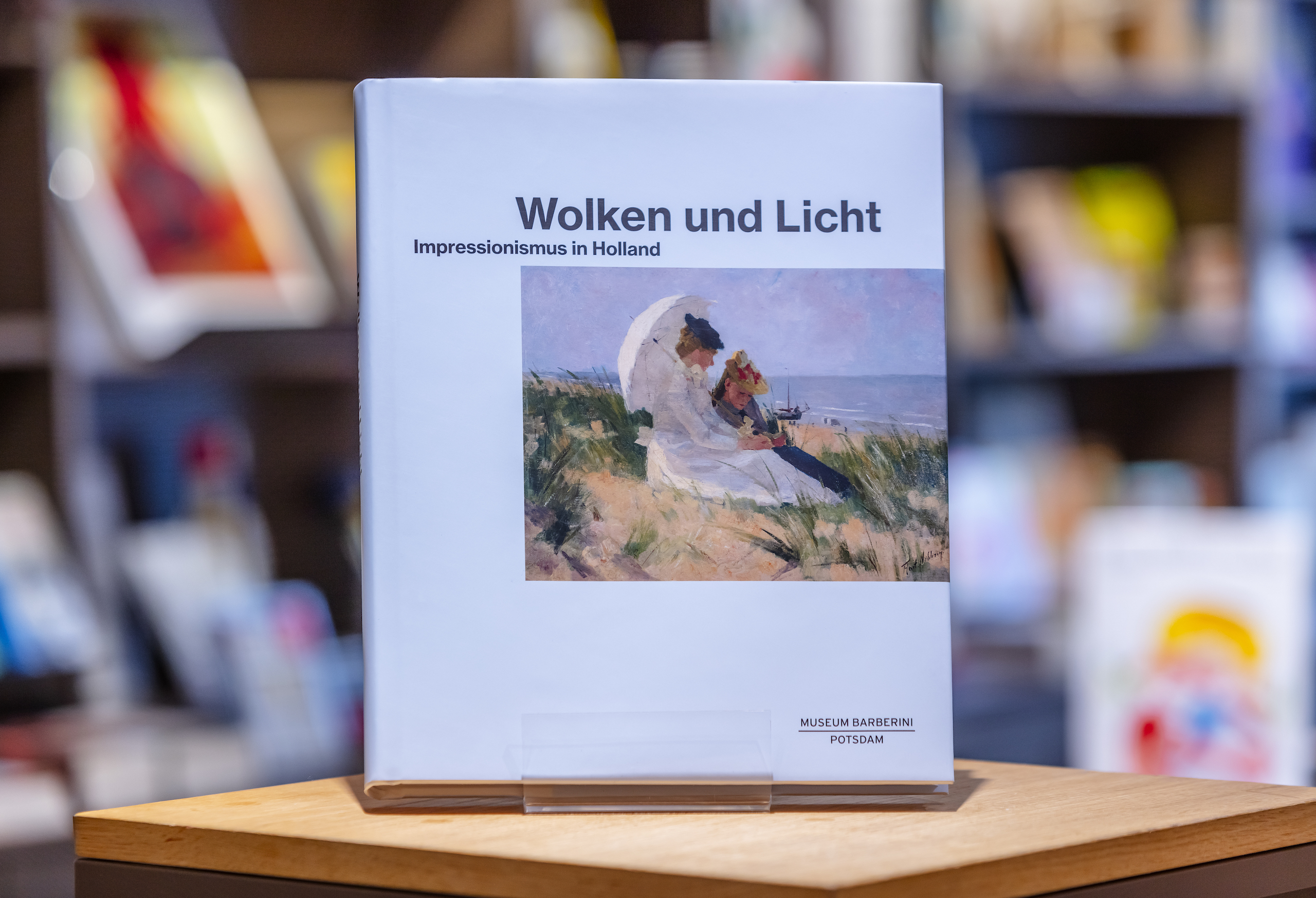

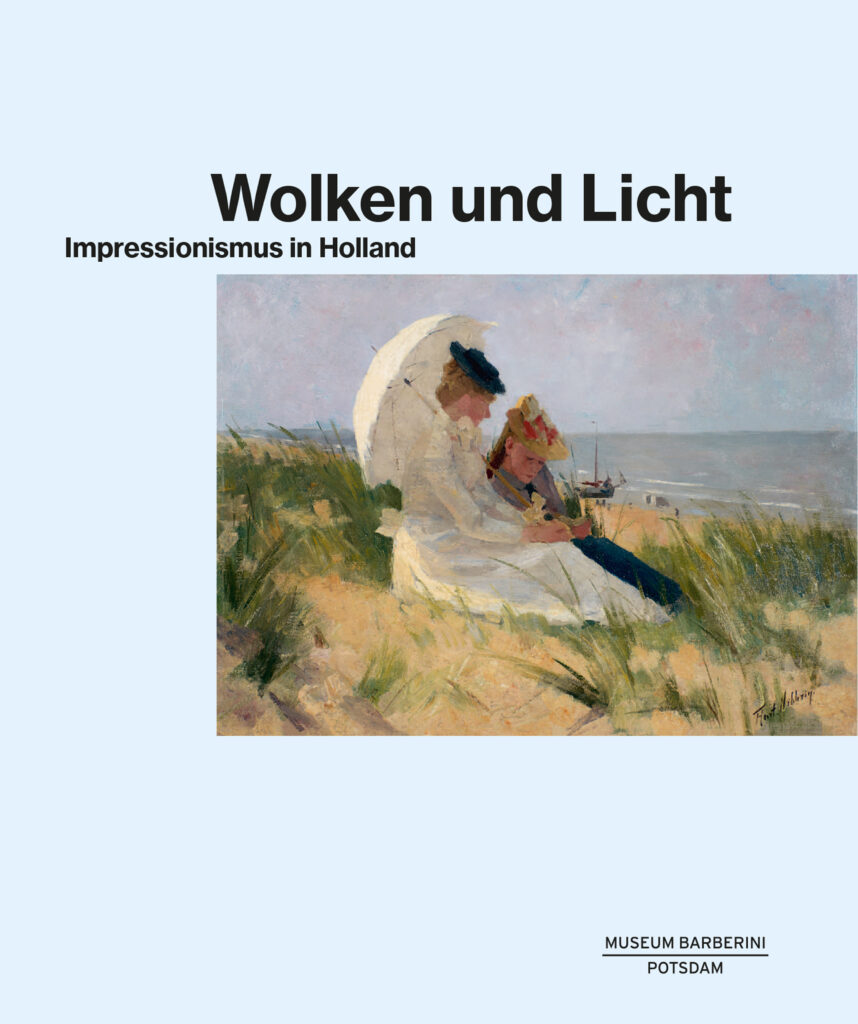

The publication accompanying the exhibition brings together numerous works by some 40 artists, including Johan Barthold Jongkind, Vincent van Gogh, Jacoba van Heemskerck, and Piet Mondrian, and, with a comprehensive look at 19th-century Dutch painting, is a nice addition to the pre- or post-exhibition visit.

From the seventeenth century, clouds, waves, and beaches belonged to the characteristic features of Netherlandish art. The French Impressionists also admired the landscape painting of the Dutch Old Masters, though their interest was focused less on identification with a national landscape than on the realism of its style. Claude Monet’s visit to the Dutch town of Zaandam in 1871 was subversive: having fled to London to escape the Franco-Prussian War, on his return journey he stayed in Holland while Paris was still occupied by Prussian troops. Monet’s role model Gustave Courbet had likewise visited Holland in the 1840s, retreating from the French art world to develop the characteristic immediacy and realism of his painting through the study of clouds and waves. Dutch artists saw the works of the Barbizon painters during visits to France. Like the French Impressionists in the forest of Fontainebleau, Dutch artists painted the light filtering through the trees in the woods of Oosterbeek as early as around 1850. The Hague School devoted itself to the polder landscape under broad skies, echoing the cloud paintings of the Old Masters. The paintings of Willem Roelofs, Anton Mauve, and Jacob Maris are characterized by luminous grays that transform the rain-heavy clouds over the meadows into the protagonists of their images. The beach is the arena of fishermen, who go out to sea or return with their catch; here, in contrast to the marine painting or ocean views of Romanticism, subjective observation is already determinative.

In the 1880s, the painters of the Hague School were succeeded by the Amsterdam Impressionists, who discovered the city as the locus of modern life with its shopping streets, coffeehouses, and electric lights. The beach now became the setting for leisure activities such as strolling or riding donkeys. Artists like George Hendrik Breitner and Isaac Israels, who knew the work of Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, and Gustave Caillebotte from exhibitions in Paris, sought out motifs of technological progress and social change in their own environment. From 1890 on, the next generation of Dutch artists drew inspiration from French and Belgian Pointillism, which they saw at exhibitions in Amsterdam and Leiden. After 1905, the landscapes created under the influence of French Fauvism soon came to be known as Luminism. Unmixed colors, expressively exaggerated in simultaneous contrasts, connect the late work of Vincent van Gogh to the early, Pointillist phase of Piet Mondrian and demonstrate that Impressionism fueled the avant-garde in Holland as well.

Nineteenth-century Dutch art is seldom shown in Germany and is scarcely represented in German museums, with the exception of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, which systematically purchased works by the Hague School in the 1880s. While such figures as Van Gogh and Mondrian have been the subject of numerous monographic exhibitions, painters like Jacoba van Heemskerck, Jan Toorop, Jan Sluijters, and many others who have been honored with major retrospectives in the Netherlands are nearly unknown in Germany —although their relationship to the landscapes of Max Liebermann and the influence of Van Gogh on the artists of Die Brücke give them an air of familiarity.

The catalog is published in English and German, 312 pages, 200 illustrations

With contributions by Renske Cohen Tervaert, Frouke van Dijke, Mayken Jonkmann, Jeroen Kapelle, and Renske Suijver, from, among others, the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam & The Mesdag Collection, The Hague, the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, and the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague.

The text is an excerpt from the catalog.

Header Image: David von Becker