Dirck Langelaer. The Court Gardener from Holland

The choice of Potsdam as a residence by Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, and the accompanying construction of the new city palace gave rise to extensive building projects aimed at beautifying the land. The palace was to be the center of a vast cultivated landscape structured by avenues, visual axes, and canals.

The elector was assisted by his confidant Prince John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen, governor of Cleves, whose residence was surrounded by sprawling gardens and who had used a network of paths and sight lines to articulate the terrain, creating a park landscape that was exceptional for the seventeenth century. A similar approach was envisioned for the new residence in Potsdam, and in August 1664 John Maurice wrote to the elector: “daß gantze Eylandt mus ein paradis werden” (“the whole island must become a paradise”).

Early efforts to create such a landscape were reflected in the atlas produced by Samuel von Suchodoletz in the 1680s. The illustration “Ichonographia oder Eigentlicher Grundriß der Churfürstlichen Herrschaft Potsdamb” (Iconographia or True Ground Plan of the Electoral Dominion of Potsdam) shows a perfectly straight street extending eastward from the city palace. This “Allee gegen Pannenberg” (avenue toward Pannenberg) led along a dike across the Havel Bay in Neustadt to a hill with a large oak tree as a point de vue. On the far side of the city canal, the “Allee gegen Eichberg” (avenue toward Eichberg) branched off, with four rows of trees leading to what is now the Pfingstberg. Today, this street axis is essentially preserved in the Lindenstraße and the Jägerallee. Only a few trees from the original planting along these avenues still survive on the Jägerallee.

Samuel von Suchodoletz: Ichonographia oder Eigentlicher Grundriß der Churfürstlichen Herrschaft Potsdamb │ Photo: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Privy State Archives)

Samuel von Suchodoletz: Eigentlicher Grund-Riß des Churfürstlichen Dorffs und Lust-Gartens Bornheim │ Photo: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Privy State Archives)

The streets were planned in 1668 by the Dutchman Dirck van Langelaer. Since the art of garden design was less fully developed in seventeenth-century Brandenburg than in the neighboring countries to the west, the elector imported not only the inspiration, but also the expert personnel. Langelaer, who came from the province of Utrecht, was born into a family of court gardeners in the service of the House of Orange and learned the craft of gardening in the Netherlands before coming to Potsdam. His presence there is first documented in 1665 in a church register in Bornim, where he was tasked with supervising the development of a new electoral garden complex. As a model farm, Bornim would become an example of ideal land management in the electorate of Brandenburg, for the cultivated landscape around Potsdam was to serve not only for adornment, but also for sustenance. The planner of the garden is unknown, but as court gardener—a position in which he was primarily responsible for the preservation and care of the trees—Langelaer tended and oversaw the complex for the rest of his life.

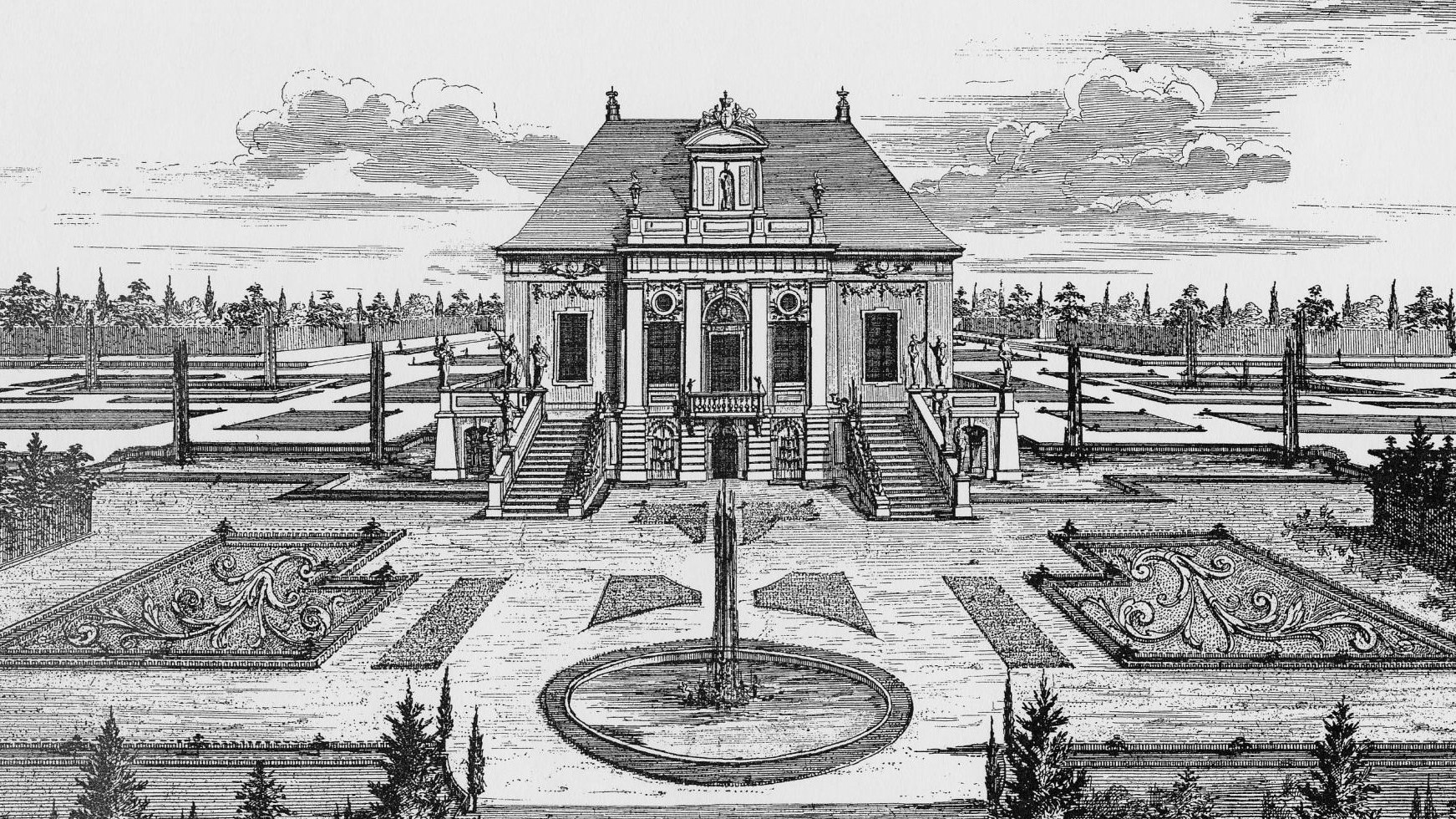

Another plan in Suchodoletz’s atlas shows the design of the garden: the rectangular complex, surrounded by a moat and accessible only by means of bridges, was both a kitchen garden and a decorative one. The orthogonal grid system accommodated beds for growing vegetables as well as ornamental parterres and fountains. An inventory made after Langelaer’s death conveys an impression of the rich variety of plants in the Bornim garden. In addition to fruits typical of the region such as apples, pears, and apricots, there were also fruit trees from Italy, France, and Holland, as well as almond and walnut trees and a nursery for the ongoing cultivation of young plants. Melons were grown in glass vessels, while the beds and paths of the complex were adorned with flowerpots. In 1678, the garden was expanded to include a small palace. Bornim Palace, which served not as a dwelling but as a place of recreation, was surrounded on three sides by a basin with artful fountains. Some distance away from the palace were fishponds, springs, and additional fountains, including a water organ. After his visit in 1686, Italian historian Gregorio Leti wrote that “in truth, [Bornim] deserves to be called a pleasure palace, for there you will see all manner of things for enjoyment and satisfaction. The garden is indeed delightful, due not only to its espaliers, groves, and trellises, but also to its variety of fountains.”1 Not far from the park was a spring, and for drainage a canal known as the Tiroler Graben, which still exists today, was dug parallel to the palace. This waterway also served as a means of transportation from Potsdam to the garden in Bornim.

Elector Frederick William must have held his Bornim court gardener in high esteem. Not only did he give him a plot of land in the center of Potsdam, he and his wife Dorothea also served as godparents for three of Langelaer’s nine children, all of whom were baptized in the city palace. The godparents of the remaining children convey a sense of the social milieu to which the gardener and his family belonged. As members of the Reformed church in Potsdam, they enjoyed close relationships with the many artists and craftsmen who, like Langelaer, had been brought to Potsdam from the Netherlands. Yet despite the offer of land in Potsdam, Langelaer spent the rest of his life in Bornim. In 1713, when he was seriously ill, he summoned the Bornim pastor, who later noted: “[He] desired that I pray with him and otherwise wish him well.”2 A few days later, the gardener was buried in the old church in Bornim. After his death and that of King Frederick I—who, like his father, continued to maintain the complex—the property was at first leased by Langelaer’s son. Lacking royal support, however, its condition deteriorated more and more, and in 1756 it was demolished under Frederick II. Today, scarcely any traces remain of the garden that once occupied the area between the Heckenstraße and the Mitschurinstraße.

– Leonie Schmidt, Museum Barberini

1 Hoeftmann, Inge und Noack, Waltraud: Potsdam in Alten und Neuen Reisebeschreibungen. Düsseldorf 1992, p. 35.

2 Broschke, Klaus: Das Lustschloss Bornim und seine Gartenanlage. Mit Beiträgen von Clemens Alexander Wimmer, Potsdam – Bornim, p. 50.

Header Image: Jean Baptiste Broebes: Bornim Palace, Potsdam Museum │ Photo: Potsdam Museum, Michael Lüder