Interplay: Erika Stürmer-Alex & Remy Jungerman

The third INTERPLAY juxtaposes a painted self-portrait by the Brandenburg artist Erika Stürmer-Alex from the Hasso Plattner Collection with a so-called grid work by the Surinamese-Dutch artist Remy Jungerman. As much as the works may resemble each other in their clarity and colorfulness, they are nonetheless different in their style and symbolism.

Distances and connections, both geographical and cultural, play an important role in this INTERPLAY. How far apart are Brandenburg and Suriname actually? How close are Germany and the Netherlands when we look at a map? And how close are the Netherlands and Suriname when we consider the colonial history? While hardly anyone speaks about the similarities between the work of the famous Dutch painters, designers, and architects of the De Stijl group and the grid patterns of Surinamese textile art, almost everyone immediately sees a reference to Mondrian and De Stijl in Remy Jungerman’s “grid works.” And why do many see A. R. Penck in Stürmer-Alex’s oeuvre? What kinds of stories do these associations tell? Who is declared a role model by whom?

INTERPLAY NO. 3 not only wants to establish a dialogue between Erika Stürmer-Alex and Remy Jungerman, but also elicit an unbiased reflection on role models and artistic canons. Art history, whether intentional or not, always generates references between styles. We’ve asked Stürmer-Alex to what extent Penck was formative for her and Jungerman the same question in relation to Mondrian.

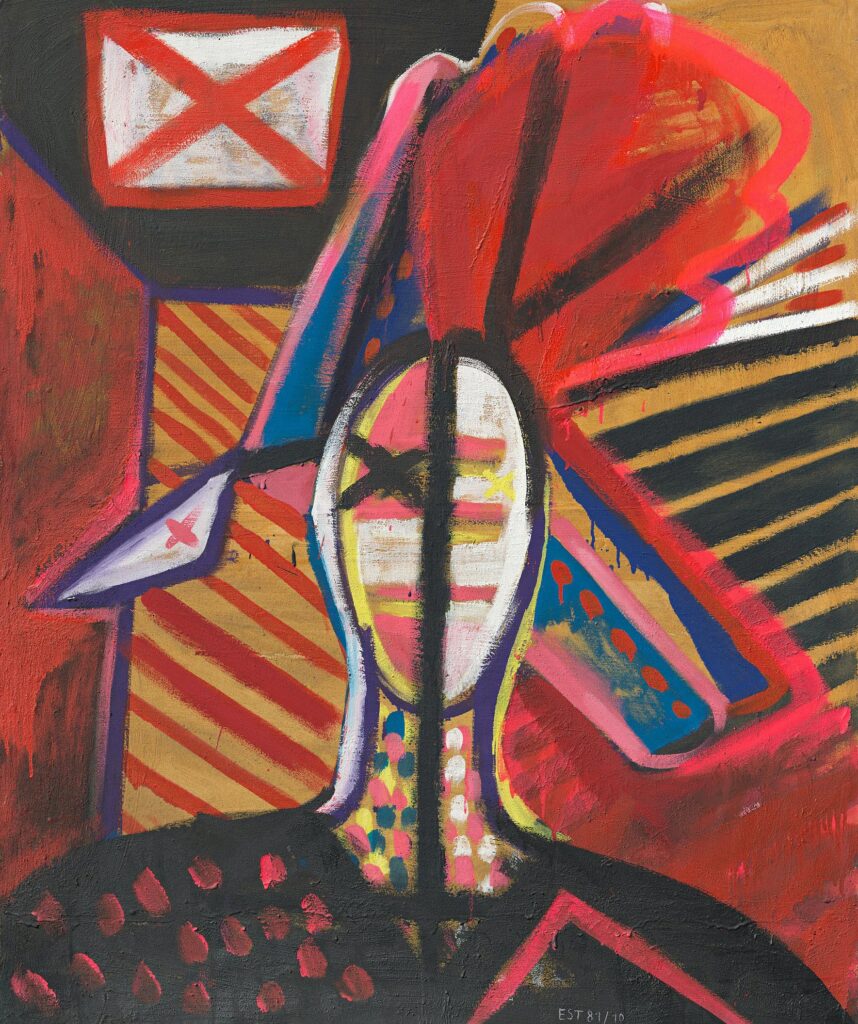

In Selbstportrait (Self-Portrait) from 1981, the artist Erika Stürmer-Alex depicts herself sign-like – without facial features, without details. Shoulders, throat, and head are roughly outlined with black paint. In addition to these black lines, the color red dominates the composition. Different abstract forms surround the artist, partially furnished with geometric patterns and simple marks like stripes, dots, and crosses. A black cross replaces one eye. Two further red crosses mark two white surfaces that resemble flags. A vertical black line divides the artist’s body into two halves.

The question of whether this is an expression of being divided in a divided Germany is answered in the negative: “I felt divided myself, not politically, but rather artistically. I was always in conflict between the expressive and the minimalistic. I made the decision: now I am resolute, now I make paintings that should look like traffic signs—yes, that’s how clear my intention was. I made a few sign-like works and then the intention was already gone again.” Erika Stürmer-Alex works intuitively. What comes across as sign-like in her work is meant to express emotional states. She says: “In the best case, the state of mind becomes visible in the work, so that I can only explain afterward what it actually probably was that depressed or delighted me there.”

The cross, according to the artist, expresses the feeling of “being crossed out.” “I felt crossed out,” she said, “even though I wasn’t. I could exhibit, but I was somehow always inhibited.” In 1981, the artist also found herself in a difficult position: she had tried to acquire a farm to develop large-format sculptures and to be able to work together with colleagues. She had arranged everything and had already begun to renovate when she received the notification that she was not permitted to buy the property because the Stasi was of the opinion that she would do group work against the state ideology. She didn’t give up, finally getting the house in a roundabout way, but she knew that she would continue to be under observation and that the farm could be taken away from her again at any moment. This time was shaped by uncertainty and a sense of being at the mercy of others. That many of us believe to recognize A. R. Penck in her work and others even assume the artist’s work had an influence on her paintings, testifies to the attempt to write a linear history of art. This may be justified visually, but Penck was neither a role model nor a friend, according to Stürmer-Alex. He had had no direct influence on her artistic work. Both came from the GDR and found a similar artistic form, far removed from the academic. He left the country as a dissident; she remained in the former East until the present day. Interestingly, both cultivated a penchant for music and a penchant for the sign-like.

In a similar vein to Stürmer-Alex’s Self-Portrait, Remy Jungerman’s “grid work” entitled Rite of Passage (2013) comprises numerous vertical and horizontal black lines created by wooden strips that are then populated with objects, collages, and cutout photographs. In his work, Jungerman uses elements related to Winti rituals in Suriname. The Winti religion includes practices that were brought by enslaved people from West Africa to Suriname. While the practice of Winti continued on Dutch plantations, it was practiced more freely, by the Maroon people, who managed to escape enslavement into the dense rainforest in the interior, where they could live out and further develop their religion.

Rite of Passage includes many bottles of different sizes: photographed bottles, printed on paper and cut out, as well as real bottles, most of them featuring different labels of Dutch liquor brands. Alcohol is used in the Surinamese religious tradition for libation, which involves the ritual pouring of a liquid as an offering to a deity or spirit or in memory of the dead. Two glass bottles standing upon wooden shelves are particularly striking. One of them contains an unidentified golden liquid, the other bears a label from the brand “Florida Water,” an eau de cologne that originated in New York, came to Suriname in the nineteenth century, and was fully integrated into the Surinamese ritual tradition in the form of baths. There is no longer liquid in the bottle, only a rolled up piece of paper – a “message in a bottle”—that refers to the transfer of objects, liquids, tastes, and smells that gradually become part of one’s culture and rituals.

Even though his “grid work” is not a self-portrait like that of Stürmer-Alex, Jungerman says it is a very personal work full of references to his origins. He sees it as a privilege to be able to trace one’s family tree through several generations and to be able to pinpoint a physical place of origin. In Jungerman’s art, origin always refers to a mixture of different cultures that meet over time and transform into something new. Of the colonial history of the Netherlands, Jungerman says: “My people’s place in the history of the Netherlands is something Dutch people are only just starting to become conscious of. I believe the fact that we are all here is due to Dutch enslavement of African people. This was created by the Netherlands, not the other way around. We have a shared history and that is something I am glad to see more people recognizing.”

According to the artist, his works draw attention to all the ancestors and to a common history full of transfer confidently and with pride: “I feel a sort of pride about my culture, rather than dwelling on our painful history. Looking at my work, which is not in your face about anything political, you can see that it can drive in all directions—it can take you to history, it can take you to the grid as well, not only Mondrian’s, but also the grids in Surinamese textiles. Or to the plantation grids during slavery that functioned as a prison—if you managed to escape one grid, there was another and another, before you could get to freedom. It was a long way to go. A lot of people managed to escape slavery and they built a new culture in the rainforest, and I’m proud of that part of my ancestry.”

It’s almost impossible to talk about the grid in art without talking about Mondrian, Remy Jungerman says: “When you use grid in your work, Mondrian will always come into the story. He owns the grid! [laughs] I hope, though, that people can look beyond Mondrian’s grid when looking at my work.” Assuming an influence without questioning and examining it is often based on a Western-influenced artistic canon that implies hierarchy and valuation. To take the time to work out similarities and differences between artists, on the other hand, can expand the view.

Erika Stürmer-Alex and Remy Jungerman share the use of the black line, primary colors, and the eye-catching cross in the form of an X. For Remy Jungerman, however, the cross doesn’t represent crossing out, but rather stability: “I’m interested in how symbols are read in different cultures, an ‘X’ may imply cancelation to Erika Stürmer-Alex and stability to me (the X in grid constructions provide stability).” The blue cross in Rite of Passage is painted with a blue pigment used in the Surinamese tradition to ward off negative energies. In Suriname, blue pigment is applied behind the ears of newborns to protect them from bad influences. This is why we decided, together with Remy Jungerman, to paint the MINSK cabinet in this very color—to protect the INTERPLAY from “the bad eye.”

– Paola Malavassi, Director, DAS MINSK Kunsthaus in Potsdam

ERIKA STÜRMER-ALEX & REMY JUNGERMAN

INTERPLAY NO. 3

03.6. – 20.8.2023

INTERPLAY is an ongoing collection format of DAS MINSK Kunsthaus in Potsdam. In each INTERPLAY, a work from the Hasso Plattner Collection encounters a work from another collection. Bringing the works together temporarily in the MINSK cabinet provides insights into the museum’s own holdings and other collections. Sometimes INTERPLAY shows similarities, and sometimes differences between art and artists. This opens up new perspectives that can only arise in the space between works of art.

All quotations come from personal conversations with Remy Jungerman on March 3, 2023, and with Erika Stürmer-Alex on April 5, 2023.