Potsdam Faience

In 1739, King Friedrich Wilhelm I founded a faience factory in Potsdam. Elector Friedrich Wilhelm had set up a first production facility 61 years earlier in Berlin with Dutch specialists. Since the founding document for this manufactory was signed in Potsdam, research into the 20th century assumed that the first manufactory was located near the river Havel instead of the Spree.

It was the the Potsdam faience specialist Paul Heiland who, among others, corrected this belief. However, Dutch influences cannot be overlooked in the Potsdam production either. They had come a long way before they could get here.

The term “faience” for white-glazed, richly decorated pottery derives from the Italian city of Faenza, which in the early modern period was an influential trading center for ceramics originally imported to Europe from the Middle East. Production facilities were set up north of the Alps from the 16th century onwards. The manufactories received a boost with the import of porcelain to Europe by the Dutch East India Company. The so-called “white gold” aroused desire, as is well known, but initially there was a problem with the production. One way of getting at least a little closer to the seemingly unattainable material was to refine the decor of ceramic products and to have a good marketing concept, especially from the Delft faience manufacturers.

Numerous potters called themselves “porcelain bakers” and thus suggested talent that went far beyond the expected. In addition, variants of the blue and white painting of Chinese porcelain were developed early on in Delft. East Asian motifs were published in template books for faience painters and enriched with regional characteristics. The catalog of motifs provided for figures dressed in loose robes in wooded, rocky landscapes with architectural elements, just as popular were purely floral motifs, including so-called “Indian flowers”, stylized lotus leaves and blossoms, loosened up by one or the other bird, preferably a peacock or heron with an elegantly curved neck (Fig. 1). The shape of the delftware was based both on everyday needs and on the luxurious taste of wealthy citizens and the nobility.

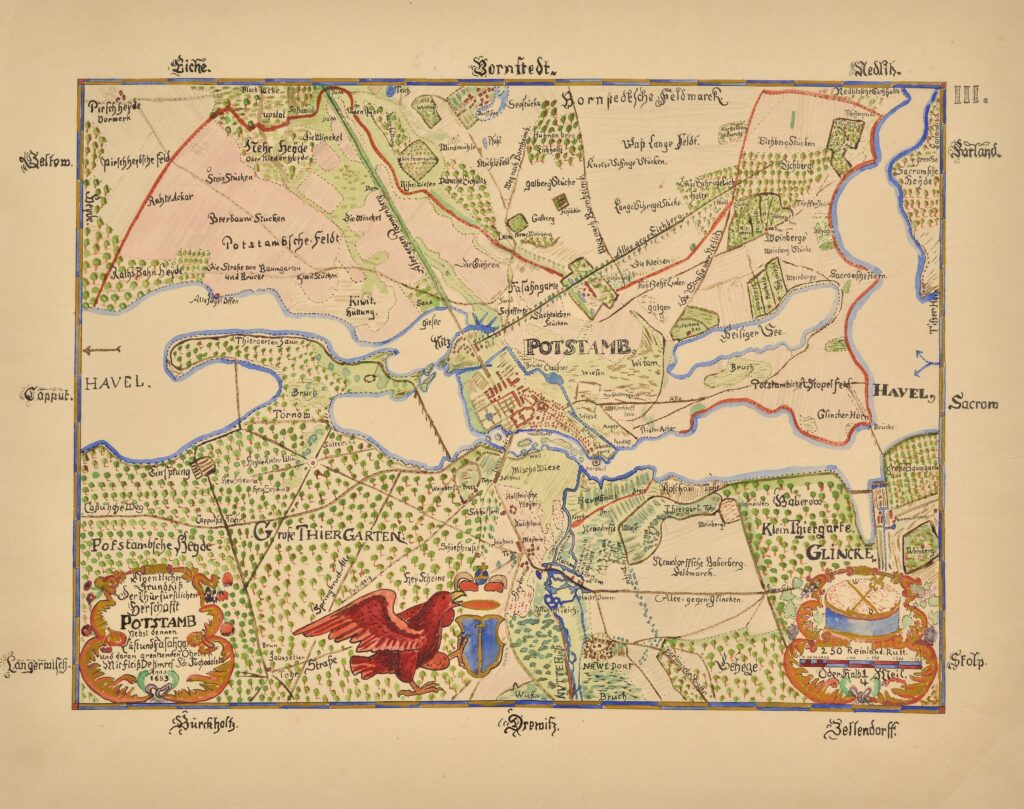

In the last quarter of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century, dozens of faience manufactories based on Dutch models were founded in German-speaking countries. In 1678 Elector Friedrich Wilhelm hired Pieter Fransen van der Lee from Delft to open a faience factory in Berlin. The contract was signed in Potsdam, the production should take place near the “Thiergarten”. Such a “Thiergarten” also existed in Potsdam; Samuel Suchodolec’s map shows it in the south of the city, today at about the height of the Albert Einstein Science Park (Fig. 2). There were no other documents proving an early Potsdam production; the objects themselves gave little further information, since the majority of the objects were not marked. It was not until the evaluation of the Berlin church registers in the 1920s by the chairman of the Brandenburg Museums Association, Georg Mirow, and publications by Paul Heiland that evidence of Berlin as the first faience manufactory in the region was found.

In fact, Potsdam only began to manufacture faience more than sixty years after it was founded in Berlin. King Friedrich Wilhelm I provided Christian Friedrich Rewendt, who was educated in Berlin, with a house in what is now Friedrich-Ebert-Straße to set up a production facility. Christian Rewendt died in 1768, his sons were less skilled producers and traders. The manufactory went bankrupt until the plasterer Constantin Sartori from Berlin took it over in 1775 and brought it to new heights. After his death in 1800, the premises were sold to two earthenware producers.

Primarily baluster-shaped vases, jugs with pewter mounts and bowls are known from Potsdam today. However, the range of products most likely fulfilled all household and table requirements. The motifs were primarily based on the products manufactured in Zerbst and Berlin in the early days, which in turn incorporated Dutch influences. For vases, primarily variations of chinoiserie decorations in blue nuances should be mentioned, supplemented by baroque ornamentation. The design of the cylindrical jugs was based on the pilaster structure (Fig. 3), which was probably first adopted for faience by the Dutchman Cornelius Funcke in Berlin. Coats of arms of guilds or mansions were also popular (Fig. 4). The adoption of the so-called “German flowers” (field flowers) from the Meißner manufactory into faience made its way via Berlin to Potsdam and became a popular motif, especially for so-called potpourri vases (Fig. 5).

The Potsdam Museum – Forum for Art and History preserves over 150 faiences in its collection. We offer you a complete overview here.

– Dr. Uta Kumlehn, Potsdam Museum – Forum für Kunst und Geschichte

Figure 1: Bowl with bird on a rock-motif, probably Dutch, 1700-1750, clay, glazed, inglaze painting, Potsdam Museum │ Photo: Holger Vonderlind

Figure 2: Plan of the Potsdam dominion, Richard Hoffmann after Samuel Suchodolec, 1928 [1683], pen and watercolours, Potsdam Museum – Forum for Art and History │ Photo: Michael Lüder

Figure 3: Roller jug with pilasters, Lüdicke Manufactory, Berlin, 1771–1773, clay, pewter, glazed, inglaze painting, Potsdam Museum │ Photo: Holger Vonderlind

Figure 4: Guild pitcher of the Potsdam bricklayers, Christian Rewendt manufactory, Potsdam, 1743, clay, pewter, glazed, inglaze painting, Potsdam Museum │ Photo: Holger Vonderlind

Figure 5: Lidded vase with floral decoration, Constantin Sartori manufactory, Potsdam, 1775–1800, clay, glazed, inglaze painting, inglaze painting, Potsdam Museum │ Photo: Holger Vonderlind