Dutch Forced Labourers in Potsdam

It seems like an irony of history: between 1941 and 1945, the district and regional court prison in the Großes Holländisches Haus (Great Dutch House) at Lindenstraße 54/55 was a place of imprisonment for Dutch men and women. They were among the several hundred forced labourers who were awaiting trial or serving sentences there.

The German occupiers had recruited, forced or coerced them – like around 7.5 million people throughout Europe – to work in Germany and transported them to work sites to compensate for the labour shortage caused by the war. In Potsdam alone were at least 70 barracks camps and other accommodations where forced labourers from East and West were forced to live – many of them located in the middle of the city and surrounded by residential buildings.

The approximately 40 Dutch prisoners, including four women, were accused of such offences as refusing to work, violations of the War Economy Ordinance, negligent physical injury and forbidden contact with war prisoners. The majority, however, were crimes such as food theft or dealing with stolen food – an indication of the poor living conditions of foreign workers.

Compared to the Eastern European workers, the Western European workers were still relatively well off. They were able to move around quite freely, sometimes lived in private quarters instead of barrack camps and were more often employed to perform skilled work. They were not immediately recognisable to the public like Eastern European forced labourers, who had to wear patches on their clothes: P for Polish origin, OST for people from the Soviet Union. There were also great differences in the punishments. Proceedings against forced labourers from Western Europe were based on German criminal law and additional regulations that also applied to the German population. For people from Eastern Europe, on the other hand, special regulations were enacted that stipulated harsher sentences including incarceration in concentration camps or death sentences.

The files of the investigation show that the imprisoned Dutchmen worked mainly in Potsdam, Brandenburg an der Havel, Kleinmachnow and Niemegk. As qualified bakers, butchers, electricians and bookbinders, some men were able to continue working in their professions; many others were assigned to the defence industry They also substituted for missing workers in municipal enterprises, for example as tram conductors. And even the nobility benefited from them, like the SA-Obergruppenführer Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia, whose garden at Villa Liegnitz in Sanssouci Park was maintained by Hendryk K. from Haarlem. The gardener was imprisoned in February 1945 after two failed attempts to escape. The approaching end of the war delayed his trial and it was dropped altogether in the summer of 1945.

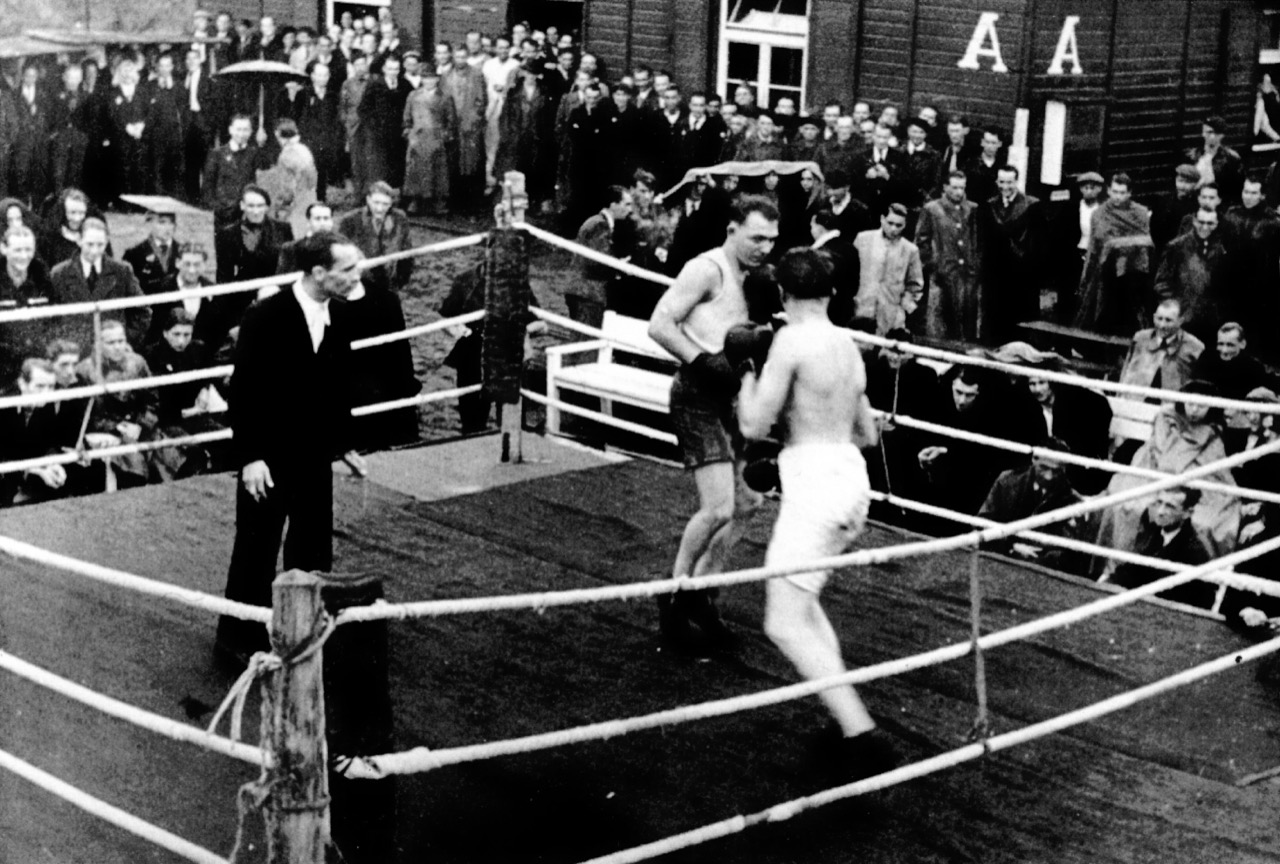

Also the film production company Ufa (Universum Film AG) in Babelsberg would not have been able to produce 60 films per year of the war without forced labourers. At first, French and Dutch prisoners of war worked in the studios. They were employed as lighting technicians, craftsmen, stagehands, decorators and in the sound department or had to maintain the grounds. In 1942, Ufa built a camp for about 600 people at the “Sandscholle” sports field in today’s Franz-Mehring-Straße. In the zones separated by razor wire lived forced labourers from the Netherlands and France as well as men, women and children from Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Poland.

At least three Dutch workers from Ufa were imprisoned in Lindenstraße: Cornelius A. was sentenced to two months in prison for theft, which he served in Lindenstraße prison in 1942. Wilhelm von der S. stood trial for homosexual acts between 1941 and 1943. The sentence and his further fate have not been handed down. Johannes K. had voluntarily enlisted in Germany in November 1940 and initially joined the Arado Flugzeugwerke Babelsberg as a painter. In 1942 he transferred to Ufa, where he began to trade in contingent products such as meat, butter and alcohol. He was fortunate and was able to avoid conviction in 1944 through illness.

However, acts classified as against the state were punished more severely even among Dutch people: Willem van E., a worker in Brandenburg/Havel, wrote to his family in 1943 that he and other foreign workers were sabotaging the production by working slowly. He also expressed his delight at the successes of the advancing Red Army. His letter was intercepted. The Potsdam district court sentenced him to three months in prison for violating the Postal Traffic Ordinance. He had intended to send the letter to his family via another address, which was forbidden. In fact, however, he was punished for his “anti-German” messages, because after his release from prison the Gestapo transferred him to a concentration camp or a so called “Arbeitserziehunglager” (work education camp). His fate remains unknown.

– Jeanette Toussaint, Stiftung Gedenkstätte Lindenstraße