The First Film about the City

Some of the oldest surviving film footage showing the city of Potsdam, its parks and palaces, can be found on a film copy from The Hague. The short film released by the Dutch production company “Nederlandsche Bioscop Maatschapij” (Nebima) has survived in the German Bundesarchiv. It was shot in 1920 and was rediscovered as recent as 2010.

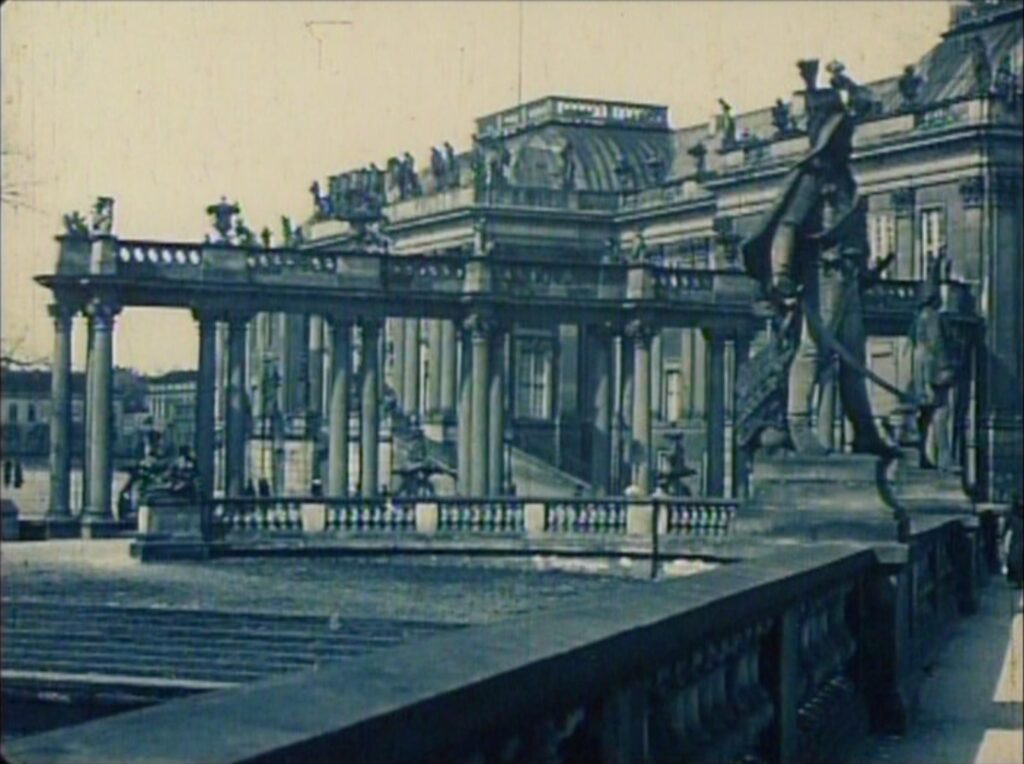

“Potsdam” contains a sequence of 14 individual motifs. In addition to Sanssouci Palace and the New Palace, attractions are: Chinese House, Belvedere, Orangery Palace, Church of Peace, etc. Only at the end does the film leave the palace grounds to depict some landmarks in Potsdam’s inner city: The Brandenburg Gate, the City Palace with “Ringerkolonnade” and the Fortuna Portal with St. Nicholas Church in the background. The Dutch Quarter or other buildings by the Amsterdam-born architect Jan Bouman were apparently of no interest to the Dutch film company.

In its use of cinematic means, “Potsdam” is extremely limited. In its use of cinematic means, “Potsdam” is extremely limited. Here and there an unobtrusive pan to show a building in its entirety, or a change in framing to emphasize architectural details. De Friedenskirche, De oranjerie, De historische molen – even the silent film’s intertitles are spartan. The camera angles are predominantly static. It almost seems as if these should not be “disturbed” by movements or people. Only now and then does a gently rippling water surface or an individual pedestrian in the background remind us that these are “moving images” and not photographs.

The sequence of tableaus appears a bit underwhelming, more like a slide show, less like the actuality films or travelogues that were popular in that time, which aimed at offering moviegoers something new, unusual, entertaining.1 “Potsdam” would have been ideal for an explanatory commentary, perhaps by a teacher. But we can only speculate about such a use of the film. Nevertheless, the short film is a unique audiovisual source that can also tell us a lot about the city’s self-image at the time, precisely because of its conventional choice of motifs and its prosaic mode of presentation. First and foremost, “Potsdam” is about the recognizability of magnificent architecture. The picturesque compositions may flatter a nostalgic viewing point. In these pictures, Potsdam is still present as the royal residence and garrison town, which in 1920 it factually longer was – since the abdication of the emperor and the Treaty of Versailles.

After the end of World War I, the city of Potsdam struggled to win back tourism. Films were a much-used form of advertisement in the tourism business then. The allure of the past was to become a magnet for visitors. The homogeneous picture painted by this film was in accordance to the efforts, e.g. of the so called Heimatschutzvereine, to preserve the “old Potsdam” and to contain the effects of modernization and industrialization. Potsdam is presented here as the “antithesis” of Berlin which was considered as the restless metropolis of modernity.2 “Potsdam” deliberately conceals the inner city, whose face had already changed considerably in recent years due to an influx of new residents, building densification and the establishment of retail stores. The city was “structurally neglected and devastated”3 proclaimed the governmental department for “Pflege der Heimatkunst” in Potsdam 1914.

The 1920 film “Potsdam” reflects contemporary efforts to preserve and market a pre-modern cityscape. This might also explain why the Dutch Quarter does not appear in the Dutch film. In the same year, a “local statute for the prevention of the defacement of the cityscape” was enacted. (Which, by the way, proved to become an immensely important building block for the city’s preservation.) The Dutch Quarter, however, belonged to the “Erste Stadterweiterung” and thus was not protected through the “Defacement Law.” The buildings of the Dutch Quarter were then conceived as “so inconspicuous and monotonous that significant artistic value could not be attributed to them”4.

– Sachiko Schmidt, Filmmuseum Potsdam

1 On the distinction between different urban film genres and their respective interpretation contexts see Uli Jung and Jeanpaul Goergen in: Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland, Stuttgart 2001/2005.

2 Armin Hanson: Denkmal- und Stadtbildpflege in Potsdam 1918-1945, Berlin Lukas Verlag 2011, 388.

3 Armin Hanson: Denkmal- und Stadtbildpflege in Potsdam 1918-1945, Berlin Lukas Verlag 2011, 69.

4 Armin Hanson: Denkmal- und Stadtbildpflege in Potsdam 1918-1945, Berlin Lukas Verlag 2011, 75.

Trailer

The complete film can be seen at Kino2online, the VoD platform of the Filmmuseum Potsdam. The musical accompaniment comes from Helmut Schulte and was played on the Filmmuseum’s Welte cinema organ.