The Great Dutch House in Lindenstraße

Built as an expression of military grandeur and royal power, today it is a reminder of political persecution and the Peaceful Revolution.

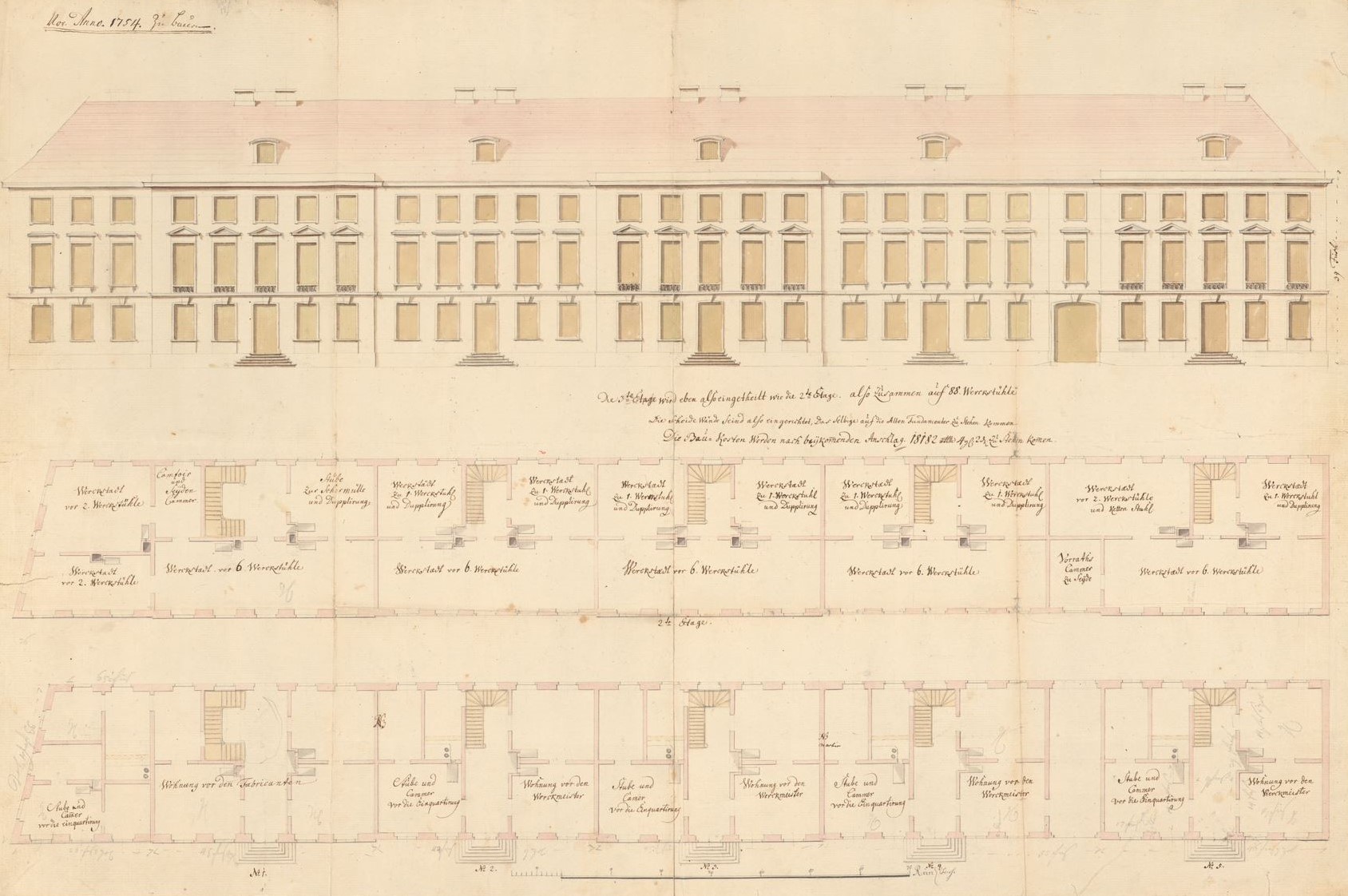

Only the bars on the house give a hint: This is no ordinary residential building. In fact, the building at Lindenstraße 54 was initially built from 1733 to 1737 as a city palace with service rooms for the commander of the royal guard. Frederick William I had declared Potsdam a garrison town when he took office in 1713. In order to relocate his regiment here, the “soldier king” had the city expanded twice. Between 1713 and 1740, the number of inhabitants rose from about 1,500 to 11,708, the number of houses from 199 to 1,154.

Frederick William I opted for the clear brick architecture of the Netherlands. This is why the Commandant’s House was also given the nickname “Great Dutch House”. The king loved his grandmother’s country and had travelled there himself several times. The master mason also came from the Netherlands. The king also recruited Dutch craftsmen for other building projects. For them he had the Dutch Quarter in Potsdam built from 1733 onwards. During the French occupation from 1806 to 1808, Napoleonic troops used the house and courtyard as a clothing depot and horse hospital. Afterwards, Potsdam’s first elected city council met here in 1809.

170 years as a court and place of imprisonment

In 1817, the city parliament moved to the town hall on Alter Markt. Due to the expansion of Potsdam’s judicial district in the mid-19th century, the Great Dutch House also had to be enlarged. For this purpose, the property at Lindenstraße 55 was purchased, newly built on and the façades of both houses were adapted in the Dutch style. In future, depending on the judicial reform, the district court, regional court or county court met here. The cell buildings were located in the rear courtyard.

The present structure of the yard was built between 1907 and 1910. The penal system was modernised and the prison was equipped with more single cells than communal cells. There was now room for around 90 inmates, separated by gender, with two separate courtyards, a prison chapel, utility buildings and a civil servants’ residence.

After the National Socialists came to power, Lindenstraße 54/55 developed into a place of ideologised and racist criminal justice. In addition to remand prisoners of the local and district court and convicted prisoners, actual and alleged opponents of the regime, Jewish people and, after 1939, several hundred forced labourers from around 23 nations, including about 40 from the Netherlands, were imprisoned here. The prison also served as a remand centre for defendants of the People’s Court, which was responsible for political offences. This court also met in Potsdam from 1943 to 1945 and passed at least 55 death sentences. A hereditary health court set up in the building in 1934 ordered the forced sterilisation of more than 3,300 people over the course of ten years on the basis of the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring”.

xx In the summer of that year, the Soviet secret service seized the building and set up the central remand prison for the state of Brandenburg here. A high board fence screened off the building. Men, women and young people were persecuted and imprisoned as National Socialists, war criminals, traitors to the fatherland, profiteers and alleged and actual opponents of the Soviet occupying power from Germany and other countries. They lived under inhumane conditions and were sentenced to harsh punishments in unlawful trials. A Soviet military tribunal met in the large hall on the ground floor and handed down more than 120 death sentences.

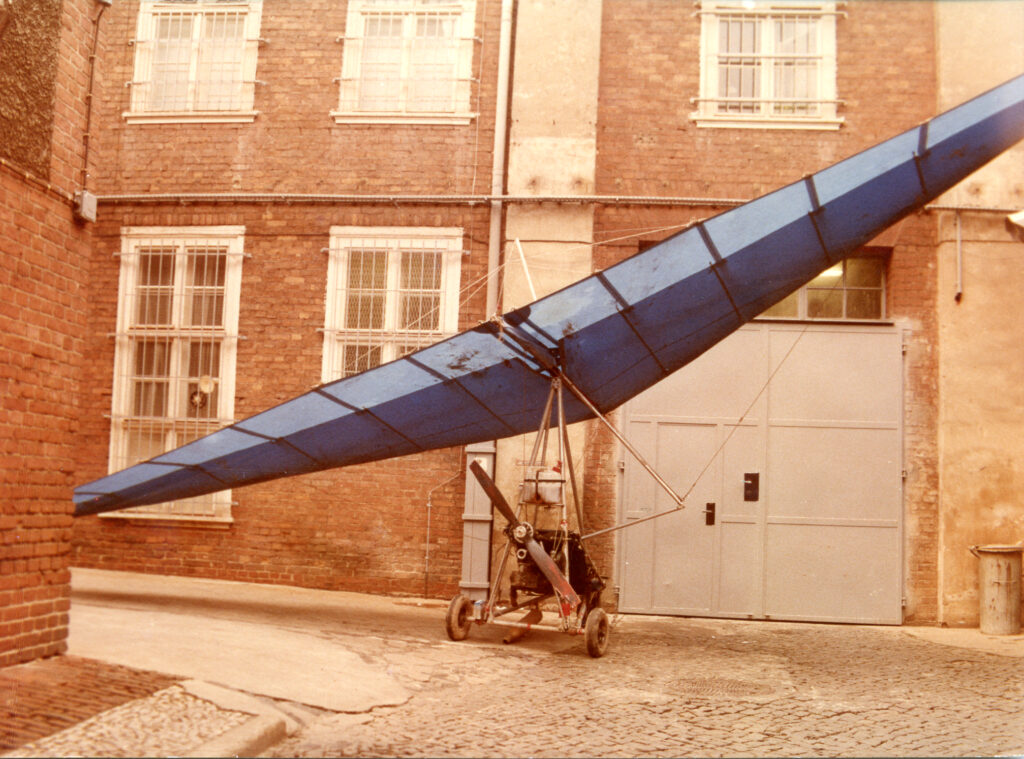

In 1952, the East German secret service took over the house as a remand prison for the GDR Ministry of State Security (MfS/Stasi) in the Potsdam district. The security perimeter was enlarged by confiscating the buildings at Lindenstraße 53 and 56, and the windows in the front building were barred. From then on, instead of the fence, signs warned people to change sides of the street. Later, a video camera monitored the pavement. The Stasi had five brick cells built in the courtyard, which could be controlled from above via a catwalk. Until 1989, almost 7,000 people, including about 1,000 women, were imprisoned in the “Lindenhotel”, as the people cynically called the house in reference to the street name. They were accused of being opponents of the state. Women and men who had tried in vain to flee the GDR after the Wall was built on 13 August 1961 or who had been criminalised because they had applied to leave the country were also held here.

House of Democracy and memorial site

In the course of the Peaceful Revolution and the GDR-wide occupations of Stasi properties in December 1989, the secret service cleared the prison. The political prisoners had already been released thanks to the amnesty of 27 October. Civil rights groups such as Neues Forum, Demokratie Jetzt, Demokratischer Aufbruch and the Independent Initiative Potsdam Women as well as the newly founded SPD now moved into the interrogation rooms in the front building. Later on, the house was used by the Department for the Preservation of Historical Monuments. With a great deal of commitment, the prison and court complex was preserved as a place of remembrance and since 1995 has been turned into a memorial and educational centre in several stages.

– Jeanette Toussaint

Header Image: Great Dutch House │ Photo: Gedenkstätte Lindenstraße, Potsdam