7.500 Tiles in Caputh

Around 7,500 blue and white tiles cover the walls and ceilings of the spacious Tile Hall in Caputh Palace. The use of these typical wares of Dutch faience production not only shows the influence of Dutch culture at the Brandenburg-Prussian court, but also represents a fine example of Baroque “tile fashion” in European palaces.

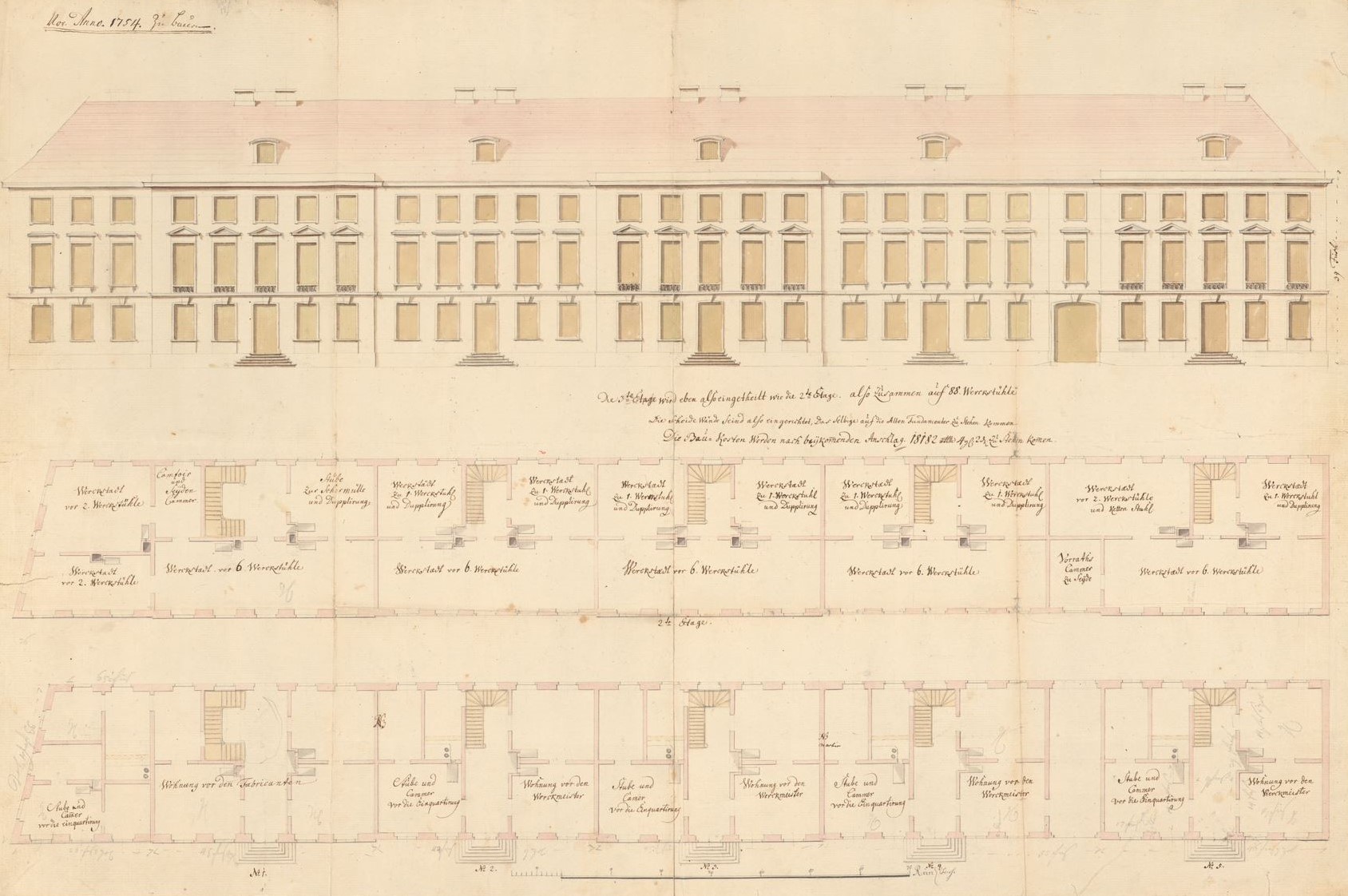

Caputh Palace, only a few kilometres from Potsdam, once belonged to Electress Dorothea and later to the first Prussian King Frederick I. The Tile Hall was not yet in existence in their time. It was not built until around 1720, when Frederick William I occasionally used the country residence of his ancestors as a place to rest on hunting trips in the game-rich surroundings. The basement room, which is tiled all around, was presumably the place where the princely hunting party went for refreshments.

Frederick William I. admired the Calvinist and at the same time bustling way of life of the Dutch. He also regarded their domestic culture as exemplary throughout his life. In Dutch town houses, faience tiles were used as a practical and yet decorative solution for covering damp or heavily used living areas such as kitchens and corridors, as skirting boards to protect the whitewashed walls and as cleanable coverings around open fireplaces and hearths. Because of their similarity to porcelain, faience tiles were increasingly appreciated and sought after in the course of the 17th century for the design of princely dining rooms and garden halls, show kitchens and bathing cabinets.

The prosperity of the United Republic of the Netherlands, which had resulted from worldwide maritime and colonial trade, had created the economic conditions for faience production, which had been established since the late 16th century. A particularly large number of pottery workshops had settled in Delft, producing bowls, plates, platters and vessels of all kinds. As “Delft faience”, they attracted a wide range of buyers throughout Europe. They were an affordable alternative to the very expensive imported porcelains from China and Japan, brought to Amsterdam by the ships of the Dutch East India Company from 1602 onwards. Its blue and white décor was also created under the influence of the sought-after East Asian porcelain. In the mid -17th century, however, other cities in the province of Holland – Rotterdam, Harlem, Amsterdam and Utrecht – developed into centres of tile manufacturing. After 1650, these tiles were also produced in the province of Friesland. The manufactories in Harlingen, Makkum and Bolsward soon took the lead in tile production. Their heyday was between 1660 and 1730. The city of Delft was only for a short time engaged in tile production, making the common name “Delft” tiles as false as the frequent confusion with the term “stove tile”. In contrast to the stove tile, the tile is a slab that is flat on both sides and does not form a cavity like the stove tile.

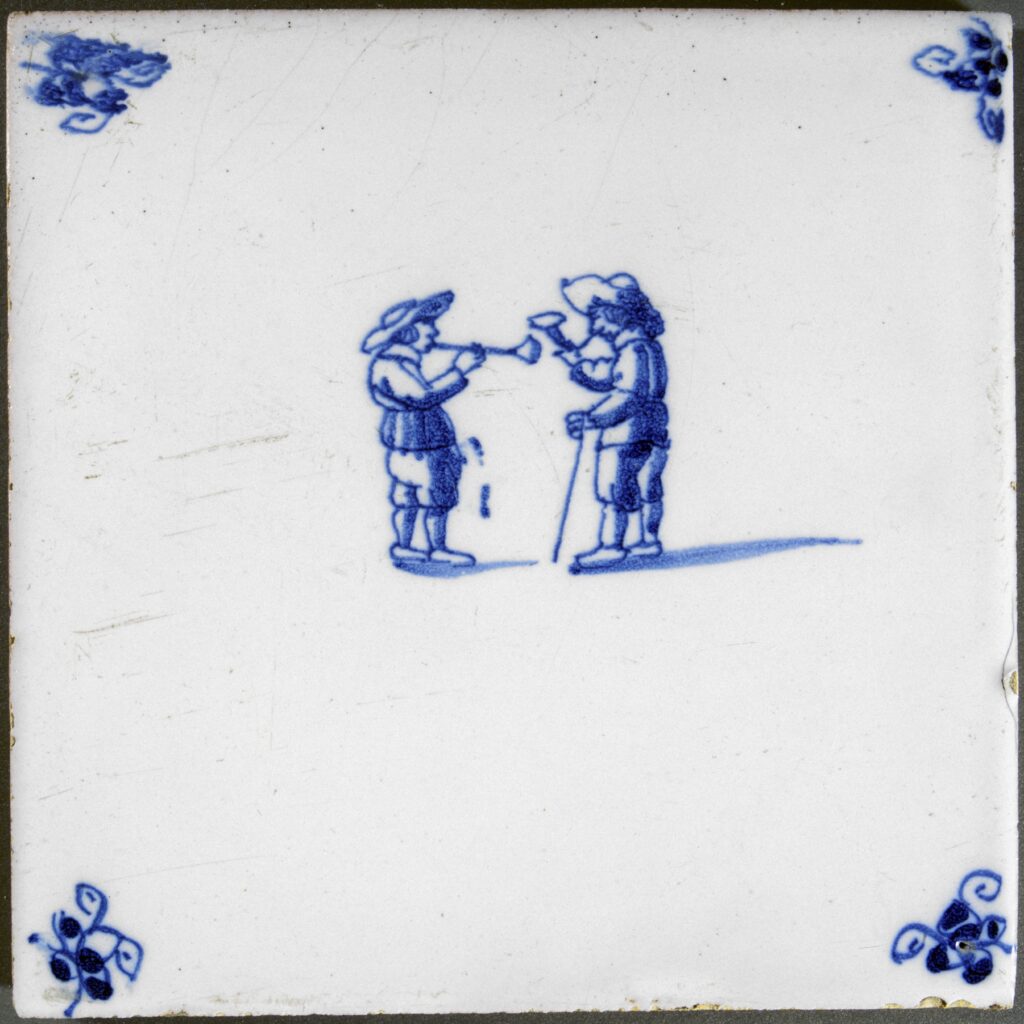

The tiles in Caputh belong to the “Nederlandse Tegels”, which were mass-produced from 1700 onwards and show variety of scenes and figures on 13 x 13 centimetres. On closer inspection of the seemingly unmanageable abundance at first sight, the tiles in the Tile Hall can be distinguished into five thematic areas with numerous variations: Sailboats, landscapes with typical landmarks such as windmills and beacons, shepherds and shepherdesses, animals in circles and small scenes from everyday life. Among them are the depictions of old children’s games, which are based on copperplate engravings or woodcuts and transferred onto the tiles. The supposedly everyday often concealed a deeper meaning that was quite familiar to the people of the 17th and 18th centuries. Games such as beating hoops and jumping rope, playing with soap bubbles or spinning tops were understood as symbols of useless activity, loss and transience.

In the Caputh Tile Hall, the symbolic meanings clearly fade into the background in the quantity of tiles and the frequent repetition of motifs in favour of the impression of the room. The attraction here lies in the complete covering of walls and ceilings. Their production must have been carried out by qualified craftsmen who were not doing such tile work for the first time. All the surfaces have a structuring arrangement and a more or less consistently followed sequence of tile motifs. The mastery of craftsmanship can primarily be seen in the execution of the ceramic cladding of the vault and transverse arches. Depending on the incidence of light, the original grout pattern and the differently tinted glazes create lively reflections on the porcelain-like surfaces. Today’s visitors can hardly escape the special atmosphere and the excitement to discover the tiles en détail in the Tile Hall of Caputh Castle.

– Claudia Sommer, Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg